The Next Big Thing is a game of literary tag. On their blogs, writers answer a few questions about a work-in-progress, then tag other writers, who do the same, tagging more writers and more–forever. It’s like a chain letter, or a pyramid scheme for people without any money, often writers!

Michael Downs, a good soul who published a great short story collection (The Greatest Show) with Louisiana State University Press, tagged me. I’ll tell you about my latest project starting with the next paragraph. And I’m tagging Steve Wiegenstein (Slant of Light) who will tell you about his Next Big Thing.

So here it is, My Next Thing, which is a way better title for this game—“Big Thing” is ridiculous if we are talking about literary fiction!

What is the working title of your novel?

You Are About to Experience Sensations You Have Never Before Known

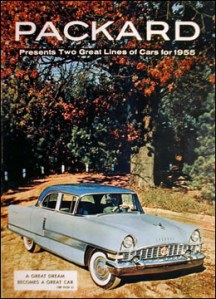

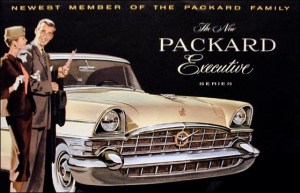

It’s an awful phrase in any context, and sounds like overblown scifi-speak, something an alien would say leading a tender babe up into his amazing saucer. The phrase was emblazoned on one of the last pamphlets Packard sent to car dealerships as that venerable American car company teetered into its death spiral. The pamphlet described the new Packard torsion suspension (prototype of what is now on a lot of trucks and SUVs). For a suspension system: You Are About to Experience Sensations You Have Never Before Known. Poor Packard: Who was going to buy a car for that?

A top of the line Packard, by the way, would have been the equivalent in expense of buying a Mercedes today, so your marketing language had really better have some hooks if you are going to compete with General Motors and its Cadillacs, which is what the buying public equated the Packards with in the 1940s and 1950s.

So, You Are About to Experience Sensations You Have Never Before Known, a really short novel, is about Maximilian Cliff, who in 1955 owns Jackson, Mississippi’s Packard Motor Car dealership; his wife, Lillian, who takes a job with the newly formed Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission against Max’s wishes; their twin children Reginald and Patricia; and their maid Dittmars. The novel ends after the riots in Oxford in 1962.

Where did the idea come from for the novel?

I am a sucker for lost things, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, biplanes, old cars, and especially the companies in America that made them and have vanished — Packard, Studebaker, Stutz, Kaiser-Frazer, Nash, Hudson. At the same time I was reading a history by James A. Ward, The Fall of the Packard Motor Car Company from Stanford University Press, we (The University Press of Mississippi, where I work) were promoting and I was reading Yasuhiro Katagiri’s The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission. Collisions ensued. Sentimentality and nostalgia over lost things can be not only dangerous but also evil. The Sovereignty Commission’s execrable role in maintaining the racial status quo and thwarting all kinds of efforts at voting and desegregation by monitoring Mississippi’s own citizens in the name of preserving “the Southern Way of Life” is a perfect example of that danger of nostalgia.

What genre does your manuscript fall under?

Literary fiction. All fiction is historical, as E. L. Doctorow said. Unless it is science fiction, fiction is about people who struggled with something, and it all happened some time ago.

Which actor would you choose to play your character in a movie rendition?

I am so lame. I can never sit through movies unless I force myself to because of directors in UPM’s Conversations with Filmmakers Series. Then, it’s my job to watch the movie, and I find it really hard even with that. So I don’t know actors names. Whoever. Some big, good-looking lug. Max is a large guy, like Jim Whitehead’s Sonny Joiner on the cover of the original novel.

What is a one-sentence synopsis of your book?

As the death knell sounds for the Packard Motor Car Company, Maximilian Cliff, once Jackson’s luxury car dealer, battles his beautiful wife Lillian, who immerses herself in the secretive and destructive Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, segregation’s watchdog.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

You know, I’m not even sure. Six months? It came together very fast, and then Sidney Thompson (Sideshow: Stories) read it for me when he was still selling new Buicks, and based on his sound advice I changed the whole thing. Sidney is a wise critic and friend. One of too many friends I never get the chance to talk to because I’m insanely busy and love my life that way.

What other books would you compare your story to within this genre?

Every book I’ll ever write about something that is lost and gone I compare (and fail and don’t measure up) to Joseph Roth’s masterpiece, The Radetzky March, which is the greatest novel I know.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

I never think two seconds about inspiration. Writing for me is all irrepressible obsession and compulsion. I have plenty to do fifty hours per week at a superb university press promoting two hundred author creations each year. There is no rational or squishily inspirational reason why I should ever write anything ever. I’m Guy Smiley, Bob Barker fifty hours each week. I’m sitting in a Newark hotel room right now and should be getting ready to present University Press of Mississippi’s list at Baker & Taylor. But when I write, I’m a raging, dangerous, unstoppable lunatic. I might look like Bob Barker, but I feel just like Jesse James.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

There’s sex and denial of sex and abstinence from sex, and heartache, and near incest. You want more? Okay, there’s racism and intrigue and buffoonery, and colossal governmental chicanery and imperial foolishness, and the ever-present human attempt to love someone even if it’s the wrong someone or for all the wrong reasons. Oh, and Packards, dozens of unsalable Packard Motor Cars!

Here’s the opening:

Maximilian Cliff, sales manager and part-owner of Jackson’s Studebaker-Packard dealership, ran his eyes along his wife’s exceptional backside in lust, anger, and sure knowledge of pending disappointment. Dressed in a crimson skirt and a black, short-sleeved blouse, Lillian Cliff smoked at the kitchen sink and blew gray proclamations toward the open window. She was about to leave for Kennington’s where she was an accounts clerk, part-time. She planned to breeze in just as the department store closed so she could pinch a few sheets of letterhead and type a note to the Governor of Mississippi. Max’s wife wanted a job with the newly formed Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission.

“You don’t have a plan, Max. I, on the other hand, do.”